About this FAQ | General Information |

||

Forecasting |

Gear and Strategy |

Safety |

Ethics |

Commerce |

Contributing |

Getting Started |

More Resources |

FAQ INDEX | |||

FAQ Last updated 17 Jan 5

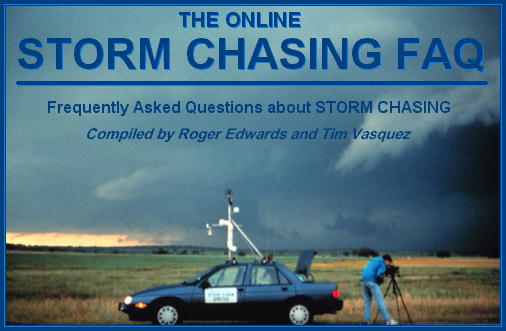

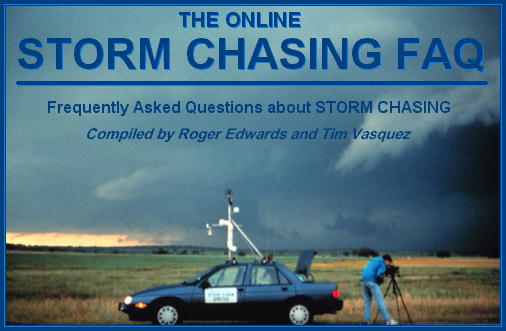

This list of Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) has been compiled on a volunteer basis from questions asked of the authors and their colleagues, as well as basic research information and countless scientific resources. More material will be added, time permitting. All the links here are intended to direct you to more detailed info on the topic linked -- often from other educational FAQs such as those at SPC and NSSL.

The Storm Chasing FAQ is not intended to be a comprehensive guide to storm observation, chasing or spotting. Instead, this a quick-reference summary, which will link you to more detailed information if you desire. The intent here is to direct you to the best storm chasing info available, regardless of whether the source is private, public or commercial. It should also be read before you post an inquiry about storm chasing to newsgroups like WX-TALK, WX-CHASE or StormTrack forums. Reading this document can save you from embarrassing moments and getting into annoying discussions.

For learning about severe storms, or if you are doing your own research or school reports, please visit the library in person. There are many good websites with tornado information also, beginning with the The Online Tornado FAQ.

DISCLAIMER: This FAQ, of course, does not recommend or endorse storm chasing. It can be a dangerous activity with the potential for damage to vehicles and other property, personal injury, disability and death. We are not responsible for if, or how, any of the information in this FAQ is used; nor are we responsible for anyone's actions in the field except our own. None of the links to outside websites implies any kind of commercial endorsement on the part of the authors, nor either StormTrack or Stormeyes, non-profit educational websites not affiliated with any particular product or service. We are not responsible for the content, accuracy, availability or timeliness of any other web sites linked from here.

What is the definition of a storm chaser?

A storm chaser is defined as a person who pursues imminent or existing

severe thunderstorms, for any reason, and operates either independently

or as part of a research effort.

What is the definition of a storm chaser?

A storm chaser is defined as a person who pursues imminent or existing

severe thunderstorms, for any reason, and operates either independently

or as part of a research effort.

BACK UP TO THE TOP

Who is a storm chaser? What are their backgrounds? Where do they come from?

Chasers are generally people from all

walks of life, most of whom are very knowledgeable about meteorology and

forecasting. Some examples of chasers' professions might include engineers,

store owners, professional photographers, pilots, programmers,

roofers, students, postal workers, and of course, meteorologists. Their average age

is about 35, but probably ranges from 18 to 65, and

women comprise

about 2% of this group. A large segment of storm chasers have a

college education. Although most live in the Plains or Midwest -- where the climatological frequency of supercells and tornadoes is highest -- storm chasers now reside in every state of the continental U.S.

Who is a storm chaser? What are their backgrounds? Where do they come from?

Chasers are generally people from all

walks of life, most of whom are very knowledgeable about meteorology and

forecasting. Some examples of chasers' professions might include engineers,

store owners, professional photographers, pilots, programmers,

roofers, students, postal workers, and of course, meteorologists. Their average age

is about 35, but probably ranges from 18 to 65, and

women comprise

about 2% of this group. A large segment of storm chasers have a

college education. Although most live in the Plains or Midwest -- where the climatological frequency of supercells and tornadoes is highest -- storm chasers now reside in every state of the continental U.S.

BACK UP TO THE TOP

Who are some storm chasers?

StormTrack has a list of storm chaser websites you may peruse, as well as dozens of other informational links.

Who are some storm chasers?

StormTrack has a list of storm chaser websites you may peruse, as well as dozens of other informational links.

BACK UP TO THE TOP

What's the difference between a spotter and a chaser?

The differences are in method and motivation. Chasers are more mobile than spotters, and unlike most spotters, travel hundreds of miles and across state lines to observe storms. Spotters' primary function is to report critical weather information, on a live basis, to the National Weather Service through some kind of local spotter coordinator. Chasers, on the other hand, may be doing it for any number of reasons, including scientific field programs, storm photography, self-education, commercial video opportunity, or news media coverage. Some storm spotters also do occasional chasing outside their home area; and some chasers are certified and equipped to do real-time spotting. For more information on storm spotting, see the StormTrack spotter page, Keith Brewster's guide, and the Skywarn FAQ.

What's the difference between a spotter and a chaser?

The differences are in method and motivation. Chasers are more mobile than spotters, and unlike most spotters, travel hundreds of miles and across state lines to observe storms. Spotters' primary function is to report critical weather information, on a live basis, to the National Weather Service through some kind of local spotter coordinator. Chasers, on the other hand, may be doing it for any number of reasons, including scientific field programs, storm photography, self-education, commercial video opportunity, or news media coverage. Some storm spotters also do occasional chasing outside their home area; and some chasers are certified and equipped to do real-time spotting. For more information on storm spotting, see the StormTrack spotter page, Keith Brewster's guide, and the Skywarn FAQ.

BACK UP TO THE TOP

How real was the movie "Twister"?

American audiences got their first real taste of storm chasing with

the release of "Twister" in 1996. Its stereotype of a storm chaser -- a thrillseeking daredevil on a frantic science mission,

racing down a rural dirt road with full-fledged tornadoes close in tow, day and night -- was outrageous fantasy.

A more accurate picture would show both professional scientists and lay people from unrelated professions, driving hundreds of miles under partly cloudy skies,

sometimes seeing violent thunderstorms, and only occasionally catching a view of a tornado. Even the "real chases" shown in documentaries and commercial videos

are just a few minutes of highlights per scene, culled from hundreds of hours of road travel. There is a nice KC Star article from 1996 on the impressions of a storm-chasing couple about the movie.

How real was the movie "Twister"?

American audiences got their first real taste of storm chasing with

the release of "Twister" in 1996. Its stereotype of a storm chaser -- a thrillseeking daredevil on a frantic science mission,

racing down a rural dirt road with full-fledged tornadoes close in tow, day and night -- was outrageous fantasy.

A more accurate picture would show both professional scientists and lay people from unrelated professions, driving hundreds of miles under partly cloudy skies,

sometimes seeing violent thunderstorms, and only occasionally catching a view of a tornado. Even the "real chases" shown in documentaries and commercial videos

are just a few minutes of highlights per scene, culled from hundreds of hours of road travel. There is a nice KC Star article from 1996 on the impressions of a storm-chasing couple about the movie.

BACK UP TO THE TOP

How often do chasers see tornadoes?

Most experienced chasers don't keep close score -- since tornadoes are only a part of the experience -- but the loose average is about 1 in 5 to 1 in 10 trips.

This, of course, depends on one's personal thresholds for what kinds of weather situations to chase, and the chaser's definition of and tolerance for busts.

Some very talented chasers willing to drive after almost any severe weather threat have gone 50 or 60 chases and several years without seeing a single tornado.

During unusually active periods, others may see several per day for up to a week. On the very rarest of days, those once in a lifetime events like 3 May 1999, a chaser may see 10 or 15 tornadoes. Others may never experience a day like that; and anyone who expects to see a tornado every trip will quickly become disappointed, frustrated and disillusioned. Tornadoes are just not very common!

How often do chasers see tornadoes?

Most experienced chasers don't keep close score -- since tornadoes are only a part of the experience -- but the loose average is about 1 in 5 to 1 in 10 trips.

This, of course, depends on one's personal thresholds for what kinds of weather situations to chase, and the chaser's definition of and tolerance for busts.

Some very talented chasers willing to drive after almost any severe weather threat have gone 50 or 60 chases and several years without seeing a single tornado.

During unusually active periods, others may see several per day for up to a week. On the very rarest of days, those once in a lifetime events like 3 May 1999, a chaser may see 10 or 15 tornadoes. Others may never experience a day like that; and anyone who expects to see a tornado every trip will quickly become disappointed, frustrated and disillusioned. Tornadoes are just not very common!

BACK UP TO THE TOP

What is a "storm chase bust"?

Simply put, a bust is a failed chase trip. But a dismal failure for one person may be the event of a lifetime for another. Only a very few consider failure to see a tornado as a bust, since tornadoes are so hard to find. Most chasers consider a trip a bust when no storms are seen -- or when an event falls far below expectations. Many chasers are so captivated by the beauty of the sky and open plains that they consider almost no storm chase trip a bust -- even when there is little or no thunderstorm activity.

What is a "storm chase bust"?

Simply put, a bust is a failed chase trip. But a dismal failure for one person may be the event of a lifetime for another. Only a very few consider failure to see a tornado as a bust, since tornadoes are so hard to find. Most chasers consider a trip a bust when no storms are seen -- or when an event falls far below expectations. Many chasers are so captivated by the beauty of the sky and open plains that they consider almost no storm chase trip a bust -- even when there is little or no thunderstorm activity.

BACK UP TO THE TOP

Why do chasers do it?

The root of almost all storm chasing is the challenge of forecasting

the storm and trying to understand its inner workings. The most dedicated chasers spend

countless hours during the cold winter months reading textbooks,

studying scientific journals, and meeting with fellow chasers to

find what makes the storm tick, or how the atmosphere producing the

storm works. is power in storm chasing, giving the extra edge to reach

more storms and encounter less busts. Not surprisingly, many chasers

are professional meteorologists, including scientists at SPC, NCAR and NSSL who chase storms on their own free time, to sharpen their first-hand understanding of storms. Tactics and strategies developed by

experienced storm chasers over the years have likewise had an

impact on what scientists know about severe weather. But of course, no sane person would spend countless hours and days

on the road just to get close to benign textbook weather systems. The

real reward is enjoying the experience of one of nature's most

violent yet beautiful phenomena -- the supercell thunderstorm. Photos and video are motivators too; but they can become

just an afterthought! Chasers may have more reasons: the chance to get

out and see the prairie, to wander through obscure towns in search of

unique photo opportunities, or just the chance to get out of the

house. For more insight, check out Dave Hoadley's timeless 1982 essay on why we do this unusual hobby.

Why do chasers do it?

The root of almost all storm chasing is the challenge of forecasting

the storm and trying to understand its inner workings. The most dedicated chasers spend

countless hours during the cold winter months reading textbooks,

studying scientific journals, and meeting with fellow chasers to

find what makes the storm tick, or how the atmosphere producing the

storm works. is power in storm chasing, giving the extra edge to reach

more storms and encounter less busts. Not surprisingly, many chasers

are professional meteorologists, including scientists at SPC, NCAR and NSSL who chase storms on their own free time, to sharpen their first-hand understanding of storms. Tactics and strategies developed by

experienced storm chasers over the years have likewise had an

impact on what scientists know about severe weather. But of course, no sane person would spend countless hours and days

on the road just to get close to benign textbook weather systems. The

real reward is enjoying the experience of one of nature's most

violent yet beautiful phenomena -- the supercell thunderstorm. Photos and video are motivators too; but they can become

just an afterthought! Chasers may have more reasons: the chance to get

out and see the prairie, to wander through obscure towns in search of

unique photo opportunities, or just the chance to get out of the

house. For more insight, check out Dave Hoadley's timeless 1982 essay on why we do this unusual hobby.

BACK UP TO THE TOP

What is the appeal of storm chasing?

Storm chasing is most accurately compared to a memorable vacation. Take all the photographs you want,

but there is simply no way to convey the fun, adventure, and challenge of intercepting storms through photographs. Yes, seeing a photogenic tornado can be the ultimate treasure find, the highlight of a season. But there is so much more! Storm chasing is the conquering feeling of a successful forecast, and the challenge of figuring out why a forecast went wrong when the skies stay blue. Chasing is a deep allure, a singular connection with nature's power, something not completely describable with words. It's manifest in fleeting moments of sensory magic, snapshots of time remembered for life: standing in the middle of nowhere under the full moon,

entranced by a sparkling storm tower while a haunting rock ballad plays through the car stereo. It's losing the view of a spectacular

storm immersed in a sea of dust...driving the 300 miles home to the

sound of a distant radio station...seeing "anvil crawler" lightning streak overhead in the rainy night sky and cast a silver glow across the landscape...feeling a tingle of anticipation while

refueling the car...seeing small cumulus erupt into a giant thunderhead nearby in less than 20 minutes...basking in the flaming orange light of a sunset sky filled with mammatus clouds...relaxing in

a local restaurant far off the beaten path...hearing the tone alarm go off on the weather radio while cruising toward the ominous, lightning-sliced pall of dark sky looming in the southwest...seeing newly planted green wheat fields, dappled with drifting cloud shadows, and rippling from horizon to horizon in the warm southerly winds...the cameraderie of friendships forged through many hours of conversation while cruising open Great Plains roadways...the bonds renewed through meeting old friends and fellow storm enthusiasts in a small-town pizza house, hundreds of miles from anyplace in particular. And all that is just the beginning of the experience...

What is the appeal of storm chasing?

Storm chasing is most accurately compared to a memorable vacation. Take all the photographs you want,

but there is simply no way to convey the fun, adventure, and challenge of intercepting storms through photographs. Yes, seeing a photogenic tornado can be the ultimate treasure find, the highlight of a season. But there is so much more! Storm chasing is the conquering feeling of a successful forecast, and the challenge of figuring out why a forecast went wrong when the skies stay blue. Chasing is a deep allure, a singular connection with nature's power, something not completely describable with words. It's manifest in fleeting moments of sensory magic, snapshots of time remembered for life: standing in the middle of nowhere under the full moon,

entranced by a sparkling storm tower while a haunting rock ballad plays through the car stereo. It's losing the view of a spectacular

storm immersed in a sea of dust...driving the 300 miles home to the

sound of a distant radio station...seeing "anvil crawler" lightning streak overhead in the rainy night sky and cast a silver glow across the landscape...feeling a tingle of anticipation while

refueling the car...seeing small cumulus erupt into a giant thunderhead nearby in less than 20 minutes...basking in the flaming orange light of a sunset sky filled with mammatus clouds...relaxing in

a local restaurant far off the beaten path...hearing the tone alarm go off on the weather radio while cruising toward the ominous, lightning-sliced pall of dark sky looming in the southwest...seeing newly planted green wheat fields, dappled with drifting cloud shadows, and rippling from horizon to horizon in the warm southerly winds...the cameraderie of friendships forged through many hours of conversation while cruising open Great Plains roadways...the bonds renewed through meeting old friends and fellow storm enthusiasts in a small-town pizza house, hundreds of miles from anyplace in particular. And all that is just the beginning of the experience...

BACK UP TO THE TOP

Are chasers drawn exclusively to tornadoes?

A tornado is a prominent goal for most while chasing, but it's very rare that

a chaser will expect to find one before it happens. Tornadoes are

icing on the cake. They're difficult to find,

even for the most experienced; and those whose one and only motivation is a tornado

become discouraged and quit. Most chasers are realistic and enjoy

any photogenic storm that they find, and if a tornado occurs, a safe distance

(a mile or more) is kept from the tornado (contrary to popular opinion).

Are chasers drawn exclusively to tornadoes?

A tornado is a prominent goal for most while chasing, but it's very rare that

a chaser will expect to find one before it happens. Tornadoes are

icing on the cake. They're difficult to find,

even for the most experienced; and those whose one and only motivation is a tornado

become discouraged and quit. Most chasers are realistic and enjoy

any photogenic storm that they find, and if a tornado occurs, a safe distance

(a mile or more) is kept from the tornado (contrary to popular opinion).

BACK UP TO THE TOP

How many storm chasers are there?

That depends on your definition of "storm chaser." The core group of the most dedicated chasers -- the people who set aside blocks of time to storm observing every spring for many years -- probably number around 100. Count students, media crews, serious but only occasional chasers, tourists, curious local residents and anyone who merely claims to be a storm chaser, and the number swells well past a thousand. Given an isolated supercell in central or western Oklahoma during May, there may be over a hundred carloads of storm chasers crowding the roadways.

How many storm chasers are there?

That depends on your definition of "storm chaser." The core group of the most dedicated chasers -- the people who set aside blocks of time to storm observing every spring for many years -- probably number around 100. Count students, media crews, serious but only occasional chasers, tourists, curious local residents and anyone who merely claims to be a storm chaser, and the number swells well past a thousand. Given an isolated supercell in central or western Oklahoma during May, there may be over a hundred carloads of storm chasers crowding the roadways.

BACK UP TO THE TOP

Who were the first storm chasers?

The late Roger Jensen is believed to be the first person who actively hunted for severe thunderstorms and tornadoes - in the upper Midwest in the late 1940s. David Hoadley, of Falls Church, VA, has been doing so annually since 1956, and is widely considered the "pioneer" storm chaser. The late Neil Ward of the National Severe Storms Laboratory was the first storm-chasing scientist, using insights gained from his field observations of tornadoes to build more complex and accurate tornado simulations in his laboratory. The first federally funded, scientific storm intercept teams fanned out from NSSL across the Oklahoma plains in 1972; but their greatest early success came a year later with their intensive documentation of the Union City, OK, tornado of 24 May 1973. This was also the first time a tornado was measured intensively by both storm intercept teams and Doppler radar -- the forerunning event to the nationwide network of Doppler radars now used for early warning.

Who were the first storm chasers?

The late Roger Jensen is believed to be the first person who actively hunted for severe thunderstorms and tornadoes - in the upper Midwest in the late 1940s. David Hoadley, of Falls Church, VA, has been doing so annually since 1956, and is widely considered the "pioneer" storm chaser. The late Neil Ward of the National Severe Storms Laboratory was the first storm-chasing scientist, using insights gained from his field observations of tornadoes to build more complex and accurate tornado simulations in his laboratory. The first federally funded, scientific storm intercept teams fanned out from NSSL across the Oklahoma plains in 1972; but their greatest early success came a year later with their intensive documentation of the Union City, OK, tornado of 24 May 1973. This was also the first time a tornado was measured intensively by both storm intercept teams and Doppler radar -- the forerunning event to the nationwide network of Doppler radars now used for early warning.

BACK UP TO THE TOP

How has storm chasing changed over time?

When the pioneers of storm chasing got started, weather

data was difficult to get and not much was known about storms. During the 1970's, the University of Oklahoma and the National Severe

Storms Laboratory began mobile storm research programs -- the most notable

of which was to deploy an instrumented package known as TOTO (totable

tornado observatory) in the path of a tornado to verify Doppler-observed

winds. It was during the 1970's when private storm chasing began catching

on, and in 1977 a small newsletter called Storm Track was started. In

the early 1980's, mobile storm research was covered by the television

program "In Search Of" and later, "Nova." By the mid to late 1980's, many

of the mobile storm research programs had ended (and TOTO was retired). Nowadays, with the exception of the recent VORTEX project, mobile storm

research is confined mainly to performing precision portable radar

observations to learn more about the small-scale structure of thunderstorms.

Chasing as recreation, however, is blooming due to increased

exposure and renewed interest through the media and Internet. Chasing has also become increasingly commercialized by hot competition for extreme storm video, increasing numbers of TV and radio station chase crews, pro photographers searching for the award-winning sky view, and even several "safari-style" storm chase tour operations.

How has storm chasing changed over time?

When the pioneers of storm chasing got started, weather

data was difficult to get and not much was known about storms. During the 1970's, the University of Oklahoma and the National Severe

Storms Laboratory began mobile storm research programs -- the most notable

of which was to deploy an instrumented package known as TOTO (totable

tornado observatory) in the path of a tornado to verify Doppler-observed

winds. It was during the 1970's when private storm chasing began catching

on, and in 1977 a small newsletter called Storm Track was started. In

the early 1980's, mobile storm research was covered by the television

program "In Search Of" and later, "Nova." By the mid to late 1980's, many

of the mobile storm research programs had ended (and TOTO was retired). Nowadays, with the exception of the recent VORTEX project, mobile storm

research is confined mainly to performing precision portable radar

observations to learn more about the small-scale structure of thunderstorms.

Chasing as recreation, however, is blooming due to increased

exposure and renewed interest through the media and Internet. Chasing has also become increasingly commercialized by hot competition for extreme storm video, increasing numbers of TV and radio station chase crews, pro photographers searching for the award-winning sky view, and even several "safari-style" storm chase tour operations.

BACK UP TO THE TOP

What kind of research do chasers usually do?

Contrary to popular belief, most chasers are not directly involved

in research. Field research in meteorology requires methods and techniques that are

meticulously carried out, so much so that they can completely

absorb the enjoyment of storm chasing. However, few would dispute that

the thousands of photos and videos collected by chasers over the past

three decades have paid valuable dividends to the science of meteorology

and to the public.

What kind of research do chasers usually do?

Contrary to popular belief, most chasers are not directly involved

in research. Field research in meteorology requires methods and techniques that are

meticulously carried out, so much so that they can completely

absorb the enjoyment of storm chasing. However, few would dispute that

the thousands of photos and videos collected by chasers over the past

three decades have paid valuable dividends to the science of meteorology

and to the public.

BACK UP TO THE TOP

Have any storm chase teams performed real research?

Yes -- most being affiliated in some way with either NSSL, NCAR or the OU School of Meteorology. Those insitiutions have been doing field work involving storm intercept teams for most of the last three decades. A few other collegiate meteorology programs have participated in individual research projects which last a year or two -- for example, the University of Mississippi's support of the "Sound Chase" program of the early 1980s. Perhaps the greatest field program ever attempted -- V.O.R.T.EX. -- was a collaboration between several university and government units. There are also several individual chasers who collect meteorological data on their own and provide it to research institutions such as NSSL. But again, the great majority of storm chasers are not participating in any kind of formal scientific study, despite the liberal use of the word "research" by many private chaser groups.

Have any storm chase teams performed real research?

Yes -- most being affiliated in some way with either NSSL, NCAR or the OU School of Meteorology. Those insitiutions have been doing field work involving storm intercept teams for most of the last three decades. A few other collegiate meteorology programs have participated in individual research projects which last a year or two -- for example, the University of Mississippi's support of the "Sound Chase" program of the early 1980s. Perhaps the greatest field program ever attempted -- V.O.R.T.EX. -- was a collaboration between several university and government units. There are also several individual chasers who collect meteorological data on their own and provide it to research institutions such as NSSL. But again, the great majority of storm chasers are not participating in any kind of formal scientific study, despite the liberal use of the word "research" by many private chaser groups.

BACK UP TO THE TOP

What is chaser convergence? A chase crowd?

Storm chasers, many of whom know each other through their shared interest and previous encounters in the field, often meet again during a chase day: at a data stop while waiting for convective development, safely parked off a remote stretch of road in the inflow region of a storm, or in some 24-hour diner at 11 pm after the end of a long chase day. That is "chaser convergence," a friendly but safe event. Much different are "chase crowds," unpleasant and often hazardous accumulations of people (many of whom are thrillseeking locals with camcorders) on the roads near a storm. Chase crowds are commonly characterized by unsafe behavior, such as parking in traffic lanes, placing equipment in roadways and blindly pulling back into traffic.

What is chaser convergence? A chase crowd?

Storm chasers, many of whom know each other through their shared interest and previous encounters in the field, often meet again during a chase day: at a data stop while waiting for convective development, safely parked off a remote stretch of road in the inflow region of a storm, or in some 24-hour diner at 11 pm after the end of a long chase day. That is "chaser convergence," a friendly but safe event. Much different are "chase crowds," unpleasant and often hazardous accumulations of people (many of whom are thrillseeking locals with camcorders) on the roads near a storm. Chase crowds are commonly characterized by unsafe behavior, such as parking in traffic lanes, placing equipment in roadways and blindly pulling back into traffic.

BACK UP TO THE TOP

How important is forecasting to chasing? What's the benefit of good forecasting ability?

The most consistently successful storm chasers are good severe storms forecasters -- whether or not they do it for a living or have formal meteorological education. They waste much less time and gasoline heading to the wrong area on busts, and often arrive in the best storm potential well before convection begins. Computer models and access to the latest watch and warning information are no substitutes for good forecast skill. Models are often wrong on the scale of severe weather, and people who chase watches and warnings often arrive late and miss much of the most photogenic parts of a storm's lifespan. Having the meteorological insight to be there when storms form is also much safer and less stressful than frantically racing a hundred miles or more toward storms which have exploded in unexpected places!

But that's not all...the best chasers also try to forecast storm motion, storm character and storm evolution with the roads and terrain of the target area in mind, in order to consider the best intercept routes and photographic angles.

While this kind of advance strategic thinking doesn't always work; over the years it can save lots of time, money and gas, garner better photos and video, and provide a less risky and more enjoyable storm chasing experience.

How important is forecasting to chasing? What's the benefit of good forecasting ability?

The most consistently successful storm chasers are good severe storms forecasters -- whether or not they do it for a living or have formal meteorological education. They waste much less time and gasoline heading to the wrong area on busts, and often arrive in the best storm potential well before convection begins. Computer models and access to the latest watch and warning information are no substitutes for good forecast skill. Models are often wrong on the scale of severe weather, and people who chase watches and warnings often arrive late and miss much of the most photogenic parts of a storm's lifespan. Having the meteorological insight to be there when storms form is also much safer and less stressful than frantically racing a hundred miles or more toward storms which have exploded in unexpected places!

But that's not all...the best chasers also try to forecast storm motion, storm character and storm evolution with the roads and terrain of the target area in mind, in order to consider the best intercept routes and photographic angles.

While this kind of advance strategic thinking doesn't always work; over the years it can save lots of time, money and gas, garner better photos and video, and provide a less risky and more enjoyable storm chasing experience.

BACK UP TO THE TOP

How does a chaser forecast the target?

That's a simple question with no simple answer, because every chaser has different methods. As a general rule, the chase day usually begins unfolding a day or two before,

as model forecasts, severe weather outlooks,

television reports, and computer model forecasts all begin hinting at an active day ahead. Chaseable severe weather requires some combination of moisture, instability, lift and wind shear -- the four ingredients all organized severe storms need, and which chase forecasters seek. A weakness in one may be compensated for by unusual strength in another; but with a glaring lack of any of those ingredients, storms may be weak or may not form at all.

Analyzing surface and upper air data is important as far out as two or three days, to determine where these ingredients are setting up and where they may shift. This continues off and on through the morning of the chase, when the target areas get narower and decisions must be made about when and where to go.

If the chaser is already in the general threat area, he/she may be able to continue analyzing weather maps, satellite pictures, upper air soundings and forecast guidance into early afternoon. The chaser is still trying to find the best combination of the four ingredients so that storms can form. Once the chase is underway, most decisions are made by looking at the

sky; although some chasers with the technology may download satellite, radar and other observational data on the road, to better pinpoint the target.

How does a chaser forecast the target?

That's a simple question with no simple answer, because every chaser has different methods. As a general rule, the chase day usually begins unfolding a day or two before,

as model forecasts, severe weather outlooks,

television reports, and computer model forecasts all begin hinting at an active day ahead. Chaseable severe weather requires some combination of moisture, instability, lift and wind shear -- the four ingredients all organized severe storms need, and which chase forecasters seek. A weakness in one may be compensated for by unusual strength in another; but with a glaring lack of any of those ingredients, storms may be weak or may not form at all.

Analyzing surface and upper air data is important as far out as two or three days, to determine where these ingredients are setting up and where they may shift. This continues off and on through the morning of the chase, when the target areas get narower and decisions must be made about when and where to go.

If the chaser is already in the general threat area, he/she may be able to continue analyzing weather maps, satellite pictures, upper air soundings and forecast guidance into early afternoon. The chaser is still trying to find the best combination of the four ingredients so that storms can form. Once the chase is underway, most decisions are made by looking at the

sky; although some chasers with the technology may download satellite, radar and other observational data on the road, to better pinpoint the target.

BACK UP TO THE TOP

What are the features chasers focus on when forecasting supercells and tornadoes later the same day?

Anything which can provide enough lift in an environment of favorable instability, moisture and wind shear is fair game. The most common target is the dryline, a boundary between dry and moist air. Warm fronts, outflow boundaries and cold fronts also may provide enough lift for severe thunderstorms, if all other factors are favorable. When the cap is strong, chasers often target intersections of boundaries (say, an outflow/dryline or warm front/dryline intersection), where there is often a local maximum in both lift and shear.

What are the features chasers focus on when forecasting supercells and tornadoes later the same day?

Anything which can provide enough lift in an environment of favorable instability, moisture and wind shear is fair game. The most common target is the dryline, a boundary between dry and moist air. Warm fronts, outflow boundaries and cold fronts also may provide enough lift for severe thunderstorms, if all other factors are favorable. When the cap is strong, chasers often target intersections of boundaries (say, an outflow/dryline or warm front/dryline intersection), where there is often a local maximum in both lift and shear.

BACK UP TO THE TOP

What causes the most "bust" chases?

This is no contest: the cap -- a layer of relatively warm and stable air above the surface which stops air parcels from rising any further and becoming thunderstorms. On some days, the cap is too weak, and a squall line quickly erupts for hundreds of miles, greatly reducing the chances of seeing a tornado from an isolated supercell. Sometimes, the cap and lift are both strong, and a few storms do form (such as the 12 May 1996 "I-70" supercell in Kansas). Other days, the cap and lift are both weak, resulting in a seemingly random pattern of chaseable storms (3 May 1999 being an extreme example!). But when the cap is too strong, nothing else matters; it's "bustola" time. Many chasers have driven home sporting a sunburn and festering with frustration when every ingredient was in place -- except enough lift to break the cap. For more details on the cap and how to analyze it, see this tutorial by Tim Marshall.

What causes the most "bust" chases?

This is no contest: the cap -- a layer of relatively warm and stable air above the surface which stops air parcels from rising any further and becoming thunderstorms. On some days, the cap is too weak, and a squall line quickly erupts for hundreds of miles, greatly reducing the chances of seeing a tornado from an isolated supercell. Sometimes, the cap and lift are both strong, and a few storms do form (such as the 12 May 1996 "I-70" supercell in Kansas). Other days, the cap and lift are both weak, resulting in a seemingly random pattern of chaseable storms (3 May 1999 being an extreme example!). But when the cap is too strong, nothing else matters; it's "bustola" time. Many chasers have driven home sporting a sunburn and festering with frustration when every ingredient was in place -- except enough lift to break the cap. For more details on the cap and how to analyze it, see this tutorial by Tim Marshall.

BACK UP TO THE TOP

Of the ingredients for severe thunderstorms, what is most important to a chaser?

Without enough of any one of them (instability, lift, moisture and shear), storms may be weak or not form at all. But most chasers are in the hunt for supercells -- the special breed of long-lived, rotating thunderstorms which tend to produce the most and strongest tornadoes. The moisture, instability and lift for thunderstorms is actually rather common in spring and summer; but to get supercells, there must be some vertical wind shear.

This is defined as a change

in wind direction and speed with height. A change in speed (like with

light surface winds and a jet stream overhead) will support severe storms,

but a change in direction, particularly in the lowest 6,000 feet of the

atmosphere, is an additional element that helps to sustain supercells. An excellent

scenario for tornadic storms is where winds are blowing at 15 knots out

of the east at the surface, out of the southwest at 40 knots at 5,000

feet, and out of the west at 50 knots at 10,000 feet. Forecasters and

chasers tend to measure wind shear using storm-relative helicity (determined using a hodograph), and

look for patterns and trends that will set up high helicity values over a

threat region. Such conditions will favor rotation in a developing storm. Of course, most supercells do not produce tornadoes!

Of the ingredients for severe thunderstorms, what is most important to a chaser?

Without enough of any one of them (instability, lift, moisture and shear), storms may be weak or not form at all. But most chasers are in the hunt for supercells -- the special breed of long-lived, rotating thunderstorms which tend to produce the most and strongest tornadoes. The moisture, instability and lift for thunderstorms is actually rather common in spring and summer; but to get supercells, there must be some vertical wind shear.

This is defined as a change

in wind direction and speed with height. A change in speed (like with

light surface winds and a jet stream overhead) will support severe storms,

but a change in direction, particularly in the lowest 6,000 feet of the

atmosphere, is an additional element that helps to sustain supercells. An excellent

scenario for tornadic storms is where winds are blowing at 15 knots out

of the east at the surface, out of the southwest at 40 knots at 5,000

feet, and out of the west at 50 knots at 10,000 feet. Forecasters and

chasers tend to measure wind shear using storm-relative helicity (determined using a hodograph), and

look for patterns and trends that will set up high helicity values over a

threat region. Such conditions will favor rotation in a developing storm. Of course, most supercells do not produce tornadoes!

BACK UP TO THE TOP

So how can a chase forecaster separate tornadic from non-tornadic supercell potential?

There are no easy answers to what environmental clues separate most tornadic supercells from the rest; but interesting tendencies have been discovered in storm-relative winds, layer shear, lifted condensation level and other sounding-based parameters in the last decade or two. This is why the most dedicated storm chasers also keep up with the science of meteorology, reading the latest severe storms conference preprints, relevant papers in American Meteorological Society journals, and historical scientific references to learn more.

So how can a chase forecaster separate tornadic from non-tornadic supercell potential?

There are no easy answers to what environmental clues separate most tornadic supercells from the rest; but interesting tendencies have been discovered in storm-relative winds, layer shear, lifted condensation level and other sounding-based parameters in the last decade or two. This is why the most dedicated storm chasers also keep up with the science of meteorology, reading the latest severe storms conference preprints, relevant papers in American Meteorological Society journals, and historical scientific references to learn more.

BACK UP TO THE TOP

What do storm chasers drive? What are the best storm chasing vehicles?

Four-wheel drive SUVs (Broncos, Explorers, Durangos) are the most popular among many chasers for their ability to handle wet, slippery conditions and dirt and gravel roads; although they do have fuel mileage and expense burdens. More frugal chasers, including students, may be seen in older sedans or even compact cars. For chasing purposes, small cars (Civics, Celicas, Escorts) generally have great mileage, but get cramped after long hauls with people and equipment; and they are less safe in the event of a crash. Some chasers use large late-model sedans (Caprices, Crown Vics) for their durability, long-distance comfort, roominess and superior safety; but such cars are also relatively low-mileage and lack four-wheel drive capabilities.

Government researchers and tour groups often use large vans; and some researchers use customized trucks for their equipment. Pickups are uncommon because of a lack of protected storage space for electronic gear. The variety of storm chasing vehicles is great; and there have been some very unusual and legendary ones.

What do storm chasers drive? What are the best storm chasing vehicles?

Four-wheel drive SUVs (Broncos, Explorers, Durangos) are the most popular among many chasers for their ability to handle wet, slippery conditions and dirt and gravel roads; although they do have fuel mileage and expense burdens. More frugal chasers, including students, may be seen in older sedans or even compact cars. For chasing purposes, small cars (Civics, Celicas, Escorts) generally have great mileage, but get cramped after long hauls with people and equipment; and they are less safe in the event of a crash. Some chasers use large late-model sedans (Caprices, Crown Vics) for their durability, long-distance comfort, roominess and superior safety; but such cars are also relatively low-mileage and lack four-wheel drive capabilities.

Government researchers and tour groups often use large vans; and some researchers use customized trucks for their equipment. Pickups are uncommon because of a lack of protected storage space for electronic gear. The variety of storm chasing vehicles is great; and there have been some very unusual and legendary ones.

BACK UP TO THE TOP

How important is good vehicle maintenance and care?

The vehicle is the most important piece of equipment; and maintaining it properly is extremely critical to chase success. That is,

unless one enjoys standing beside an overheated, steaming heap of junk, in the middle of Motley County, Texas, 20 miles from the nearest town while a big supercell recedes off into the distance. Besides the mere annoyance of being stranded away from the action, breakdowns can cause chasers to lose control of their car or

become stuck in a dangerous area of the storm. Chase vehicles don't have to look good; but they must run at peak performance. This means checking and changing all fluids and filters at the manufacturer's recommended intervals, along with all the tune-ups, tire rotations, tire changes and other check-ups for which car owners are responsible. [Any chaser unfamiliar with his/her vehicle's owner's manual is irresponsible.] Always stow plenty of emergency supplies on board for safety and rudimentary repairs. Such supplies can include: flat tire inflation spray, a small fire extinguisher, a properly inflated spare tire (in case of uninflatable flats), screwdrivers and wrenches compatible with the car's parts, a road flare, flashlight with spare batteries, motor oil, coolant, transmission and power steering fluids, brake fluid, extra wiper blades, jumper cables, spare belts and hoses, hose repair kits and/or suitable tape, extra headlights and tail lamps, and a tow chain. At least one chaser on every crew should be familiar with making basic emergency auto repairs.

How important is good vehicle maintenance and care?

The vehicle is the most important piece of equipment; and maintaining it properly is extremely critical to chase success. That is,

unless one enjoys standing beside an overheated, steaming heap of junk, in the middle of Motley County, Texas, 20 miles from the nearest town while a big supercell recedes off into the distance. Besides the mere annoyance of being stranded away from the action, breakdowns can cause chasers to lose control of their car or

become stuck in a dangerous area of the storm. Chase vehicles don't have to look good; but they must run at peak performance. This means checking and changing all fluids and filters at the manufacturer's recommended intervals, along with all the tune-ups, tire rotations, tire changes and other check-ups for which car owners are responsible. [Any chaser unfamiliar with his/her vehicle's owner's manual is irresponsible.] Always stow plenty of emergency supplies on board for safety and rudimentary repairs. Such supplies can include: flat tire inflation spray, a small fire extinguisher, a properly inflated spare tire (in case of uninflatable flats), screwdrivers and wrenches compatible with the car's parts, a road flare, flashlight with spare batteries, motor oil, coolant, transmission and power steering fluids, brake fluid, extra wiper blades, jumper cables, spare belts and hoses, hose repair kits and/or suitable tape, extra headlights and tail lamps, and a tow chain. At least one chaser on every crew should be familiar with making basic emergency auto repairs.

BACK UP TO THE TOP

What are chasers doing about shooting video?

Most storm chasers carry at least one video camera as a central component of their equipment, for documenting the storms. Those who market their video may spend thousands of dollars on professional grade video cameras in state-of-the-art digital or betacam formats. Most chasers, however, still use VHS, SVHS, 8 mm or Hi-8 home camcorders; although Digital-8 and DV are becoming inexpensive enough for mass use. Digital video, Digital-8, Hi-8 and SVHS have the greatest resolution and may produce commercial quality video. Still, even the best equipment can't compensate for lousy technique and a lack of knowledge. Chris Novy offers a large and comprehensive list of tips for shooting storm video; and Dave Blanchard has some tips for scientific quality video.

What are chasers doing about shooting video?

Most storm chasers carry at least one video camera as a central component of their equipment, for documenting the storms. Those who market their video may spend thousands of dollars on professional grade video cameras in state-of-the-art digital or betacam formats. Most chasers, however, still use VHS, SVHS, 8 mm or Hi-8 home camcorders; although Digital-8 and DV are becoming inexpensive enough for mass use. Digital video, Digital-8, Hi-8 and SVHS have the greatest resolution and may produce commercial quality video. Still, even the best equipment can't compensate for lousy technique and a lack of knowledge. Chris Novy offers a large and comprehensive list of tips for shooting storm video; and Dave Blanchard has some tips for scientific quality video.

BACK UP TO THE TOP

What are chasers doing about still photography?

Not as much as in bygone years, with the advent of video cameras. Consistently high-quality still film photography is a degree of difficulty above shooting video -- and perhaps even more sensitive to lack of skill and understanding on the part of the photographer. However, the 35 mm slide still carries greater resolution than any videotape or digital imaging available; and a few chasers have even begun to use medium-format cameras. Recommended camera gear includes multiple 35 mm removable lens cameras with fixed 50 and 28 mm lenses, along with fixed or adjustable zooms out to about 200 mm. Fumbling around with multiple lenses and filters can be difficult and annoying in the heat of the moment, when a tornado churns along in a field several miles away; therefore, a well-organized accessory kit is a must for the serious photographic storm chaser. As for photographic technique, there are as many pieces of advice as there are photographers; however, there are some basics of high-quality still photography which apply to shooting storm scenes. Veteran chaser Chuck Doswell offers outdoor photography advice, as well as a landmark guide to lightning photography. As for cameras and lenses, most name brands (e.g., Canon, Mamiya, Pentax, Minolta, etc.) are good bets; and great bargains can be obtained from second-hand sources like pawn shops and auctions. Fuji E6 films (Velvia, Sensia, Provia) are favored by most chasers; however Kodachrome remains a trusty, durable workhorse in many film photography circles. High-end professional digital cameras have begun to rival 35 mm film and medium-format resolution but remain unaffordable to most storm aficionados. Consumer digital equipment, while of unsuitable grain for commercial or large-print use, are handy ways to document storm scenes for timely uploading to the web or for home printing.

What are chasers doing about still photography?

Not as much as in bygone years, with the advent of video cameras. Consistently high-quality still film photography is a degree of difficulty above shooting video -- and perhaps even more sensitive to lack of skill and understanding on the part of the photographer. However, the 35 mm slide still carries greater resolution than any videotape or digital imaging available; and a few chasers have even begun to use medium-format cameras. Recommended camera gear includes multiple 35 mm removable lens cameras with fixed 50 and 28 mm lenses, along with fixed or adjustable zooms out to about 200 mm. Fumbling around with multiple lenses and filters can be difficult and annoying in the heat of the moment, when a tornado churns along in a field several miles away; therefore, a well-organized accessory kit is a must for the serious photographic storm chaser. As for photographic technique, there are as many pieces of advice as there are photographers; however, there are some basics of high-quality still photography which apply to shooting storm scenes. Veteran chaser Chuck Doswell offers outdoor photography advice, as well as a landmark guide to lightning photography. As for cameras and lenses, most name brands (e.g., Canon, Mamiya, Pentax, Minolta, etc.) are good bets; and great bargains can be obtained from second-hand sources like pawn shops and auctions. Fuji E6 films (Velvia, Sensia, Provia) are favored by most chasers; however Kodachrome remains a trusty, durable workhorse in many film photography circles. High-end professional digital cameras have begun to rival 35 mm film and medium-format resolution but remain unaffordable to most storm aficionados. Consumer digital equipment, while of unsuitable grain for commercial or large-print use, are handy ways to document storm scenes for timely uploading to the web or for home printing.

BACK UP TO THE TOP

What other equipment is commonly taken on storm chases?

The variety of chase equipment is almost limitless; however, some of the same basic components can be found in most chasers' vehicles. Besides cameras and camcorders, basic gear can include: 2-meter and/or weather radios, scanners, miniature TVs, tripods (for still and video cameras), microcassette recorders (for documenting times and locations of severe weather, photos and video scenes), first-aid kits, state and national road atlases, plastic bags (for litter and protecting cameras from dust and rain), and extra film, batteries and videotape. Many chasers have onboard PCs or laptops, cellular phones, GPS tracking, two-way radios (for communicating with other vehicles of a caravan), power adapters and splitters, anemometers, thermometers and hygristors, window-mounting camera brackets, built-in camera holders, and much more.

What other equipment is commonly taken on storm chases?

The variety of chase equipment is almost limitless; however, some of the same basic components can be found in most chasers' vehicles. Besides cameras and camcorders, basic gear can include: 2-meter and/or weather radios, scanners, miniature TVs, tripods (for still and video cameras), microcassette recorders (for documenting times and locations of severe weather, photos and video scenes), first-aid kits, state and national road atlases, plastic bags (for litter and protecting cameras from dust and rain), and extra film, batteries and videotape. Many chasers have onboard PCs or laptops, cellular phones, GPS tracking, two-way radios (for communicating with other vehicles of a caravan), power adapters and splitters, anemometers, thermometers and hygristors, window-mounting camera brackets, built-in camera holders, and much more.

BACK UP TO THE TOP

Where do most storm chasers go?

The hub of activity is in central and western Oklahoma, into parts of northwest Texas and the eastern Texas

Panhandle. This area has by far the most tornadoes per unit area on the

planet; and it also tends to have open spaces for good viewing at a distance. Kansas and eastern Colorado are also favored for the same reasons. Some chasers

venture further north into Nebraska and South Dakota during the late spring and early summer

months, when the climatological trend of severe thunderstorms shifts northward. There are regional storm chasers from coast to coast, and even in a few other countries.

Where do most storm chasers go?

The hub of activity is in central and western Oklahoma, into parts of northwest Texas and the eastern Texas

Panhandle. This area has by far the most tornadoes per unit area on the

planet; and it also tends to have open spaces for good viewing at a distance. Kansas and eastern Colorado are also favored for the same reasons. Some chasers

venture further north into Nebraska and South Dakota during the late spring and early summer

months, when the climatological trend of severe thunderstorms shifts northward. There are regional storm chasers from coast to coast, and even in a few other countries.

BACK UP TO THE TOP

When is chasing done?

Severe storms are most common in the central and southern Plains -- where viewing is best -- during the spring period. March storms

often lack much instability or move too fast to chase effectively. April brings some of

the first chasable weather, and by May the storms are usually moving

slowly enough and instability is at its peak. This continues into the

first half of June; but afterwards, the wind fields tend to weaken in the central and southern Plains

and the best supercell activity shifts into the northern

Plains. Some chasers go to Colorado in July to chase hailstorms and so-called "landspout" tornadoes, which are fairly

common there during that month. Overall, the last half of May is

statistically the best time to chase. A small secondary peak (within a week or two) of

chaseable severe weather sometimes occurs in the Plains in late September or

early October. For more details, see Bobby Prentice's analysis of peak chaseable storm periods.

When is chasing done?

Severe storms are most common in the central and southern Plains -- where viewing is best -- during the spring period. March storms

often lack much instability or move too fast to chase effectively. April brings some of

the first chasable weather, and by May the storms are usually moving

slowly enough and instability is at its peak. This continues into the

first half of June; but afterwards, the wind fields tend to weaken in the central and southern Plains

and the best supercell activity shifts into the northern

Plains. Some chasers go to Colorado in July to chase hailstorms and so-called "landspout" tornadoes, which are fairly

common there during that month. Overall, the last half of May is

statistically the best time to chase. A small secondary peak (within a week or two) of

chaseable severe weather sometimes occurs in the Plains in late September or

early October. For more details, see Bobby Prentice's analysis of peak chaseable storm periods.

BACK UP TO THE TOP

What's the hardest part of many chases? How important is good decision-making?

The ideal chase day is where towering cumulus begins bubbling up

near a chase team in a clear blue sky, but it's almost never this easy.

Often chasers are unable to see the sky due to haze or low cloud layers,

or must contend with deciding which of several impressive storms will

become severe. Other times, any storms are too far away to see. The hardest part of chasing is being out in the middle of nowhere

at 3 in the afternoon, wondering if, where, and when the storms will

develop. Make-or-break decisions are made here, and they are what

separate the beginners from the experts. Intuition, skill, meteorological knowledge and blind luck

all influence whether one will decide to continue driving, go another

direction, or stop and wait. The decision can easily make the difference

between being 5 miles away from a developing tornado or 50 miles. Some

chasers get an extra advantage by using state-of-the-art tools such

as laptops, satellite links and cellular phones to get the latest "feel" on the developing

weather situation. But there are also a number of highly experienced and

respected storm chasers who shun most of the gadgets and

simply read the sky to formulate their tactics.

What's the hardest part of many chases? How important is good decision-making?

The ideal chase day is where towering cumulus begins bubbling up

near a chase team in a clear blue sky, but it's almost never this easy.

Often chasers are unable to see the sky due to haze or low cloud layers,

or must contend with deciding which of several impressive storms will

become severe. Other times, any storms are too far away to see. The hardest part of chasing is being out in the middle of nowhere

at 3 in the afternoon, wondering if, where, and when the storms will

develop. Make-or-break decisions are made here, and they are what

separate the beginners from the experts. Intuition, skill, meteorological knowledge and blind luck

all influence whether one will decide to continue driving, go another

direction, or stop and wait. The decision can easily make the difference

between being 5 miles away from a developing tornado or 50 miles. Some

chasers get an extra advantage by using state-of-the-art tools such

as laptops, satellite links and cellular phones to get the latest "feel" on the developing

weather situation. But there are also a number of highly experienced and

respected storm chasers who shun most of the gadgets and

simply read the sky to formulate their tactics.

BACK UP TO THE TOP

Do chasers use watch boxes to chase?

Not the most consistently successful ones. SPC tornado and severe thunderstorm watches are issued

a few hours or less before a severe

weather episode unfolds, which doesn't give the chaser enough time to

get in a good chase position unless storms erupt nearby. Furthermore, watches cover too broad of

an area for a chaser to effectively cover. They are designed not for storm chasers, but for emergency managers and the general public to prepare for the posssibility of severe weather. However, they often serve

as confirmation of what's going on. If a tornado watch

is issued for where a chaser lives, it may alert him or her to a developing

situation. The chaser will then retrieve data and decide on a specific

destination before venturing out.

Do chasers use watch boxes to chase?

Not the most consistently successful ones. SPC tornado and severe thunderstorm watches are issued

a few hours or less before a severe

weather episode unfolds, which doesn't give the chaser enough time to

get in a good chase position unless storms erupt nearby. Furthermore, watches cover too broad of

an area for a chaser to effectively cover. They are designed not for storm chasers, but for emergency managers and the general public to prepare for the posssibility of severe weather. However, they often serve

as confirmation of what's going on. If a tornado watch

is issued for where a chaser lives, it may alert him or her to a developing

situation. The chaser will then retrieve data and decide on a specific

destination before venturing out.

BACK UP TO THE TOP

When does a chase end?

Almost all chasers call off the pursuit

at dusk and get back home or motel around midnight -- sometimes later. This means chasers will often

cover up to 500 miles in a day. Some chasers will stop at least several miles from the storm to get lightning photos before heading back; but there is a risk of a deadly lightning strike anywhere near thunderstorms.

When does a chase end?

Almost all chasers call off the pursuit

at dusk and get back home or motel around midnight -- sometimes later. This means chasers will often

cover up to 500 miles in a day. Some chasers will stop at least several miles from the storm to get lightning photos before heading back; but there is a risk of a deadly lightning strike anywhere near thunderstorms.

BACK UP TO THE TOP

What and where do chasers eat?

Most chasers consume the fatty convenience-store and fast food diet when on the road, in the interest of saving time; however, nutritious eating is not difficult for those willing to run into a local full-service grocery store. Non-perishable groceries can be a great way to save money and maintain healthy eating habits; but the lure of a steaming-hot Allsup's burrito is powerful. After the chase day ends, many chasers can be found congregating in the nearest major town's buffet-style eatery (e.g., Golden Corral or Sirloin Stockade); and 24-hour diners such as Denny's and Kettle are also popular. One of the unique advantages to chasing -- which has nothing to do with weather -- is the opportunity to sample amazingly flavorful local cuisine -- say, a from a German family restaurant in a small Iowa town, or a nostalgic road shack in west-central Texas serving up mesquite-smoked pit barbecue.

What and where do chasers eat?

Most chasers consume the fatty convenience-store and fast food diet when on the road, in the interest of saving time; however, nutritious eating is not difficult for those willing to run into a local full-service grocery store. Non-perishable groceries can be a great way to save money and maintain healthy eating habits; but the lure of a steaming-hot Allsup's burrito is powerful. After the chase day ends, many chasers can be found congregating in the nearest major town's buffet-style eatery (e.g., Golden Corral or Sirloin Stockade); and 24-hour diners such as Denny's and Kettle are also popular. One of the unique advantages to chasing -- which has nothing to do with weather -- is the opportunity to sample amazingly flavorful local cuisine -- say, a from a German family restaurant in a small Iowa town, or a nostalgic road shack in west-central Texas serving up mesquite-smoked pit barbecue.

BACK UP TO THE TOP

What are the most dangerous things about storm chasing?

The greatest dangers to storm chasers are not tornadoes, but instead, traffic crashes and lightning. Driving in heavy rain, high wind, dust and/or hail is obviously dangerous, even to the experienced chaser. The only known death of a chaser during an intercept happened in 1985, when an OU student slid off a wet road while trying to avoid a large animal. Even the most careful and conscientious driver may have problems under severe weather conditions -- such as misjudging distance or hydroplaning. The solution should be obvious: Slow down on wet roads, watch for obstacles, animals and other vehicles in unusual and unsafe places; and drive very slowly whan making turns on wet surfaces. Given the hazards -- and the proliferation of inexperienced and reckless drivers around storms, it may be a matter of great fortune that more deaths haven't happened from vehicle wrecks.

Lightning is especially insidious because you may never see or hear the bolt which kills you. Even when it doesn't kill, lightning can cause ugly and horrifying aftereffects which may linger for a lifetime and cause permanent disability. Several chasers have been struck by lightning; fortunately, none have died yet. Numerous others have had terrifyingly close calls. Simply being around a thunderstorm implies a heightened lightning danger, as Gene Moore, Chuck Robertson and others discovered on one infamous chase. But good lightning safety practices minimize the threat -- namely, staying inside the closed vehicle whenever possible, and when outside, avoiding being the highest target and touching metal wiring.

What are the most dangerous things about storm chasing?

The greatest dangers to storm chasers are not tornadoes, but instead, traffic crashes and lightning. Driving in heavy rain, high wind, dust and/or hail is obviously dangerous, even to the experienced chaser. The only known death of a chaser during an intercept happened in 1985, when an OU student slid off a wet road while trying to avoid a large animal. Even the most careful and conscientious driver may have problems under severe weather conditions -- such as misjudging distance or hydroplaning. The solution should be obvious: Slow down on wet roads, watch for obstacles, animals and other vehicles in unusual and unsafe places; and drive very slowly whan making turns on wet surfaces. Given the hazards -- and the proliferation of inexperienced and reckless drivers around storms, it may be a matter of great fortune that more deaths haven't happened from vehicle wrecks.

Lightning is especially insidious because you may never see or hear the bolt which kills you. Even when it doesn't kill, lightning can cause ugly and horrifying aftereffects which may linger for a lifetime and cause permanent disability. Several chasers have been struck by lightning; fortunately, none have died yet. Numerous others have had terrifyingly close calls. Simply being around a thunderstorm implies a heightened lightning danger, as Gene Moore, Chuck Robertson and others discovered on one infamous chase. But good lightning safety practices minimize the threat -- namely, staying inside the closed vehicle whenever possible, and when outside, avoiding being the highest target and touching metal wiring.

BACK UP TO THE TOP

How can I practice good storm chasing safety?

In general, be alert, aware and have a backup plan for every situation. Dr. Chuck Doswell has prepared an excellent website with storm chasing safety rules which every chaser should know.

How can I practice good storm chasing safety?

In general, be alert, aware and have a backup plan for every situation. Dr. Chuck Doswell has prepared an excellent website with storm chasing safety rules which every chaser should know.

BACK UP TO THE TOP

Why isn't the tornado the most dangerous thing about storm chasing?

Most storms targeted by chasers are LP (low precipitation) or CL (classic) supercells, where the main updraft regions are well-defined, and the development of wall clouds and rapid rotation indicate the presence of a mesocyclone. Even in HP (heavy precipitation) supercells, a dense "bear's cage" of rotating precipitation curtains marks the most dangerous area. So with a little experience, most chasers quickly learn to recognize the areas of a supercell where tornadoes form, and can avoid getting beneath them.

Why isn't the tornado the most dangerous thing about storm chasing?

Most storms targeted by chasers are LP (low precipitation) or CL (classic) supercells, where the main updraft regions are well-defined, and the development of wall clouds and rapid rotation indicate the presence of a mesocyclone. Even in HP (heavy precipitation) supercells, a dense "bear's cage" of rotating precipitation curtains marks the most dangerous area. So with a little experience, most chasers quickly learn to recognize the areas of a supercell where tornadoes form, and can avoid getting beneath them.

BACK UP TO THE TOP

What is "core punching," and is it risky?

Sometimes, the shortest route between the chaser and the target is a region of heavy precipitation (rain and hail), the core. Penetrating the heavy precipitation area of a storm is core punching -- and can be very dangerous because of:

What is "core punching," and is it risky?

Sometimes, the shortest route between the chaser and the target is a region of heavy precipitation (rain and hail), the core. Penetrating the heavy precipitation area of a storm is core punching -- and can be very dangerous because of:

Are winds a threat?

It doesn't matter much whether winds come from a tornado or a downburst, if they are strong enough to overturn a chase vehicle or blow out windows.

Winds are a grave risk to inexperienced chasers who get too close to

a threat area or are not observing trends in the storm's behavior.

It's easily avoided by carefully choosing routes when near a storm

and staying aware of the most dangerous downdraft and mesocyclone areas.

Are winds a threat?

It doesn't matter much whether winds come from a tornado or a downburst, if they are strong enough to overturn a chase vehicle or blow out windows.

Winds are a grave risk to inexperienced chasers who get too close to

a threat area or are not observing trends in the storm's behavior.

It's easily avoided by carefully choosing routes when near a storm

and staying aware of the most dangerous downdraft and mesocyclone areas.

BACK UP TO THE TOP

What kind of threat is hail?

Some chasers enjoy the sight and sound of large hail -- as long as it is not pounding their vehicles. Besides the obvious danger to vehicles and outdoor equipment, giant hail can kill. On 30 March 2000, a softball-size hailstone killed a young man (not a chaser) in Fort Worth.

Falls of baseball-sized hail in

China have been known to kill hundreds of unsheltered people within

five minutes; while on the Great Plains, hailstorms

have left dead livestock behind. Likewise, the chaser can become fair

game if venturing outside in hail. [It has been said that storm chasers are hard-headed; but our skulls are not that different from anyone else's! :-)]

Hail can also pose a traffic hazard by covering a roadway and reducing traction, and by causing hail fog, which temporarily limits visibility. Hail danger can be prevented

if the chaser is familiar with road networks and is attentive to

storm trends and structure.

What kind of threat is hail?

Some chasers enjoy the sight and sound of large hail -- as long as it is not pounding their vehicles. Besides the obvious danger to vehicles and outdoor equipment, giant hail can kill. On 30 March 2000, a softball-size hailstone killed a young man (not a chaser) in Fort Worth.

Falls of baseball-sized hail in

China have been known to kill hundreds of unsheltered people within

five minutes; while on the Great Plains, hailstorms

have left dead livestock behind. Likewise, the chaser can become fair

game if venturing outside in hail. [It has been said that storm chasers are hard-headed; but our skulls are not that different from anyone else's! :-)]

Hail can also pose a traffic hazard by covering a roadway and reducing traction, and by causing hail fog, which temporarily limits visibility. Hail danger can be prevented

if the chaser is familiar with road networks and is attentive to

storm trends and structure.

BACK UP TO THE TOP

Should storm chasers be concerned about flash flooding?

Absolutely! Supercells -- especially HPs -- are notorious flash flood producers, as are the thunderstorm complexes and squall lines many chasers encounter during their return to home base at night. Swollen playas (kettle lakes on the southern High Plains) and streams overflowing rural roads have aborted many promising chases. At night, the danger is higher because drivers often do not see flooding across a road until it is too late to avoid driving into the water. Chasers' cars have been flooded out, stranding them; though none have been seriously injured or killed yet.

Should storm chasers be concerned about flash flooding?

Absolutely! Supercells -- especially HPs -- are notorious flash flood producers, as are the thunderstorm complexes and squall lines many chasers encounter during their return to home base at night. Swollen playas (kettle lakes on the southern High Plains) and streams overflowing rural roads have aborted many promising chases. At night, the danger is higher because drivers often do not see flooding across a road until it is too late to avoid driving into the water. Chasers' cars have been flooded out, stranding them; though none have been seriously injured or killed yet.

BACK UP TO THE TOP

Is night chasing a problem?

Night chasing is an easy danger to avoid if you simply quit

chasing at twilight. Only a very few chasers remain

active at night, except for lightning photographers maintaining a considerable distance from the storms. Night

chasing is like core punching, in that it requires extreme vigilance, awareness of winds and storm behavior, and

experience to avoid downbursts, hail shafts, and tornadic circulations. Even some very experienced and respected chasers have almost lost their lives to tornadoes, floods, unexpected severe wind, animals in the road, and lightning while roaming the roads after dark.

Is night chasing a problem?

Night chasing is an easy danger to avoid if you simply quit

chasing at twilight. Only a very few chasers remain

active at night, except for lightning photographers maintaining a considerable distance from the storms. Night

chasing is like core punching, in that it requires extreme vigilance, awareness of winds and storm behavior, and

experience to avoid downbursts, hail shafts, and tornadic circulations. Even some very experienced and respected chasers have almost lost their lives to tornadoes, floods, unexpected severe wind, animals in the road, and lightning while roaming the roads after dark.

BACK UP TO THE TOP

What does the vehicle have to do with chase safety?